How to use the terminal

What’s the simplest way to interact with a computer? No, not moving the mouse and clicking boxes on screen. You’re used to it now, but the computer is doing a lot of work for this. Imagine you don’t have a screen, only a printer and a keyboard. What’s an even simpler way of telling the computer what you want?

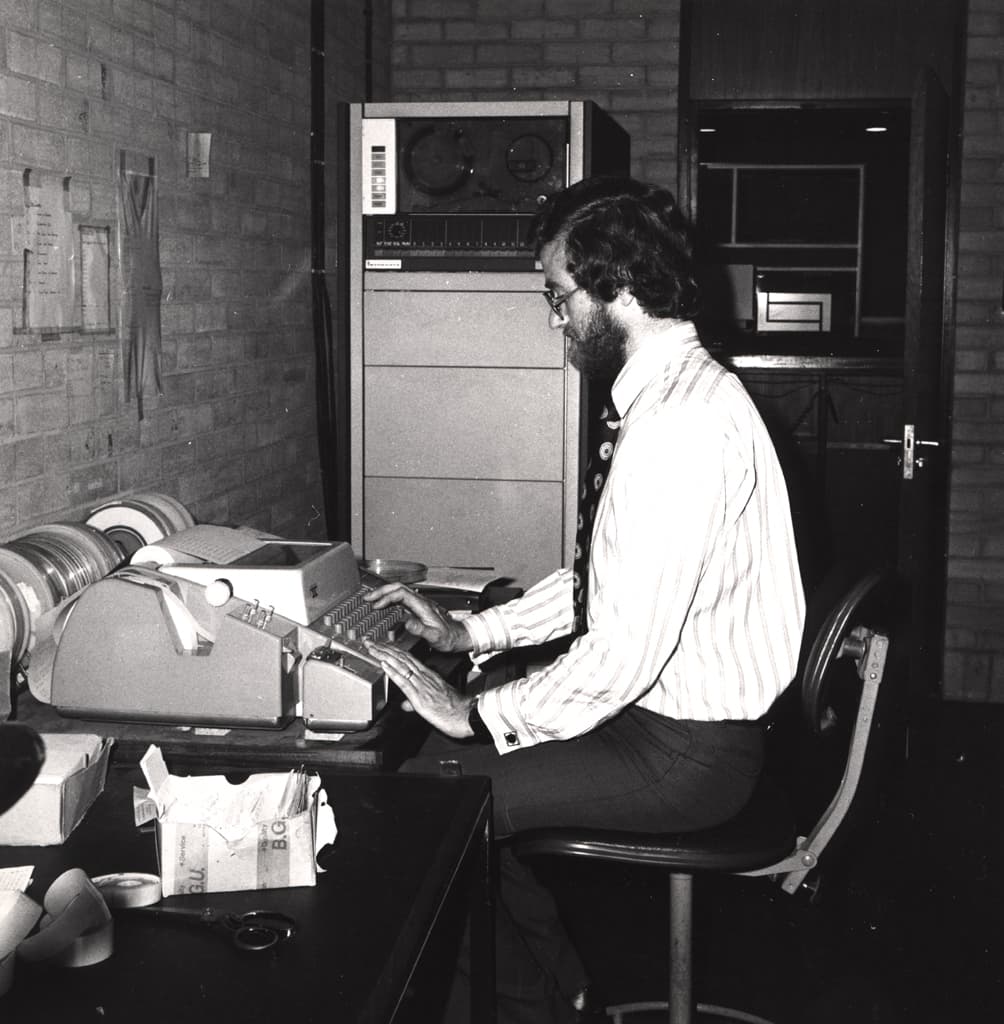

In 1975, you could use this typewriter-like machine called a teleprinter to use a computer. There’s no screen, but it can print onto the piece of paper sticking out from the top. The actual computer is visible in the background.

from Flickr by Newcastle Libraries under public domainThe simplest method is text. Write what you want.

That’s exactly what the terminal does. You write what you want and the computer writes back. Even though this idea is really simple, it works so well that it is still being used today!

As a quick sidenote, terminals are sometimes also called consoles or shells. Most of the time, people mean the same thing. Technically there is a difference. A shell is the part that does the actual work. A terminal is the setup you use to access the shell, for example a keyboard and screen or a teleprinter. A console was a special type of terminal that would typically be plugged into a special port of the computer. Now that everything is software, the distinction between terminal and console is blurred.

Programs: What can I ask for?

To copy a file you tell the computer “copy this file to there.” To let it list you all files in a folder you tell it “list everything with all info.” To remove a folder, you tell it “remove this folder and everything in it.”

Ok, I lied a bit. Unfortunately, computers don’t yet reliably understand the way we talk and write. But we can simply structure our questions in a certain manner—meet them halfway. To do the things mentioned before, you really write is cp thisFile.txt there.txt, ls -l and rm -r thisFolder.

What’s going on there? The idea is that you call a program and describe how it should do its job. So the copy program, cp, needs to know which file to copy where. ls wants to know whether it should present the files in a compact list or a table with all information. And rm needs to know that it is dealing with a folder and should really delete everything inside.

You tell a program how to do its job using arguments. You’ll notice that there are two types of arguments. There were the file names and there was this thing with the dash in front, e.g. -l. Some programs expect their arguments in a specific order. For example, cp wants the file to copy first and then the destination to copy it to. Other times you have to specify what kind of argument you are giving. ls takes many different arguments, for example to also show hidden files, -a. So these arguments have names that typically start with a dash.

What does the answer look like? If you’re lucky, nothing. Seriously. For example, if cp does its job, it gives no output. Only if it could not copy a file, e.g., because the file you wanted to copy does not actually exist, will it print what the problem was. So don’t panic if you don’t see a confirmation. Of course, programs like ls are an exception to this. Their job is to print out information to you.

Paths: Moving around files and moving files around

Imagine you sat in front of an old teleprinter. Literally a printer where you typed on a keyboard and it would print out the response line by line. So you couldn’t just drag a file to the trash bin on a video screen to delete it, and you couldn’t open a folder and see previews of the images inside.

Instead, the terminal is always in a working directory. By default it opens your user folder. If the working directory contains a file readme.txt, then you could remove it simply by giving its name, rm readme.txt. This works, because the terminal looks up file names relative to its working directory.

How do you open the file findme.txt that’s inside the folder hiddenStuff? You can tell the terminal how to get to the file using a path. In our example, the path would be hiddenStuff/findme.txt. So you tell the terminal which folders to go into, separated by slashes, /, and then you give it the file name. If you want to remove a file that is multiple folders away, the command could look like rm firstFolder/secondFolder/thirdFolder/file.txt.

All of these paths are relative to the working directory that the terminal is currently inside of. So all your images are available, but what if you need to access your USB drive? That is not inside your user folder. How do you access those?

The paths I showed you are relative. But of course every file has a unique path when you start at the first folder, the root directory. The homework.txt on your USB drive is available at /dev/sda1/homework.txt. So if you start at the root folder, your USB drive is available inside the dev folder and then inside the sda1 folder. Every path that starts with a slash is an absolute path that start at the root directory! Paths that start with a folder or file name are relative paths that start at the working directory.

Relative paths can also be written as ./hiddenStuff/findme.txt, because . is a kind of name for the current directory which in the beginning is the working directory! You could do weird stuff like hiddenStuff/./findme.txt which says “From the working directory, go into the hiddenStuff folder, then go into the current folder (you’re already in the current folder, duh!) and then there is the file findme.txt.”

But there is also a more useful name which is that of the parent directory, called ... So hiddenStuff/../otherFile.txt says “From the working directory, go into hiddenStuff, then go back to its parent folder (which is the working directory where we came from) and then there is the file otherFile.txt.” So that path is the same as findme.txt or ./findme.txt.

Now it gets interesting because we change the working directory. The program that “changes directory” is cd. So to remove a file in the hiddenStuff folder, you can call rm hiddenStuff/findme.txt or you can go into the folder with cd hiddenStuff and then remove the file with rm findme.txt. Note that these are now two commands. But if you use ls you’ll see that it will list different files as before, because you are in a different folder! So if you need with a lot of files from hiddenStuff, then cd is useful because it makes the path shorter. How do you get back? Well, you go to the parent directory with cd .. which in our example takes you back to your user folder.

Help: man, what can I do?

Since people are lazy, they try to keep everything short. “Copy” becomes cp, “list” becomes ls, “show all files, including hidden ones” becomes -a. So it might be a bit difficult to guess or even remember how everything was called exactly.

But luckily, most programs have a “manual” on how to use their programs. And it’s available as a terminal program, man! If you forget how to use cp, man cp will list you all options that are available. Many programs also offer a flag that displays some helpful information, typically called --help. So cp --help will show you what flags and options are available and how it’s used. There is no better one, those are just two different ways that programs might give you help.

You also need to know how to read certain aspects of the help text. As an example, here is a snippet of what ls --help returns:

Usage: ls [OPTION]... [FILE]...

List information about the FILEs (the current directory by default).

Sort entries alphabetically if none of -cftuvSUX nor --sort is specified.

Mandatory arguments to long options are mandatory for short options too.

-a, --all do not ignore entries starting with .

-A, --almost-all do not list implied . and ..

--author with -l, print the author of each file

-b, --escape print C-style escapes for nongraphic characters

... let's skip some ...

-l use a long listing format

... let's skip the rest ...The first thing it tells you is how you have to write it, its usage. First ls, then optionally multiple options, then optionally multiple files. The square brackets in [OPTION] indicate, that it’s an optional argument; you can also leave it out. The ellipsis, ..., tells you that you can put multiple options after each other.

After the usage, it gives an overview. It also gives more information on the FILE that showed up in the usage. Sometimes there’s different ways you can call a program, for example if it has subcommands. All possibilities will be listed and explained in the following text.

Then comes a list of all possible options. Some options have short names (one dash, one letter, e.g. -a), some have long names (two dashes, more letters, e.g. --all), some have both and you can choose. So ls -a and ls --all do the same thing. There is no shorthand for ls --author and no long version of ls -l, though.

If the option needs more information, it takes a so-called “argument”. Sometimes, options that take no arguments are called flags. They are usually used to turn on something. For example, --all is a flag that turns on listing of normally hidden files that start with a ..

If you specify multiple options or files, you need to separate them with spaces. ls --all -l first-file second-file is good, but just like you the computer can’t read ls --all-lfirst-filesecond-file, it all looks like one big argument!

Of course there is an exception: You can mash short options together, e.g. ls -al. Not to be confused with ls --all, notice the dashes! So everything following a single dash are shorthand options. Their order does not matter, so ls -al and ls -la do the same thing.

Rights: sudo, I’m begging you

Obviously, not everyone should be allowed to read and copy your homework. Only you have the copyright! Similarly, access to files on a computer is typically restricted by rights. Some files are specially protected to prevent the wrong people from using them.

The downside is that the computer does not know if it’s really you bashing the keyboard. So you use a password that (presumably) only you know to log into your account.

Certain files shouldn’t be modified by accident, because they are used by the system. If something wrong happens to them, your computer might crash! But if you know what you do, you might need to use those files anyway; or you ask a program to do it.

Installing new software on your Ubuntu (that’s a Linux operating system flavor) happens with the apt program. But not everyone should be allowed to install software, only the owner of the computer, known as the “administrator”. To prove that you are the admin, you have to enter the password.

But logging out from your typical account, loggin in with the admin account, installing the software, and then switching accounts back again is really tedious. So Ubuntu has the sudo mechanism. It let’s you switch the accounts very quickly and just one command as the admin.

The first time you use sudo apt install awesome-software, it will ask for your password. If you entered it correctly, it will run apt install awesome-software with admin rights. Then the terminal is back under your account. It will even remember the password for a while, so running sudo apt install other-thing won’t bother you with the password again. But when you close the terminal and reopen it, you’ll need to enter the password again.

Pipes: All for one, one for all

You can make programs work together! What one programs prints out, you can feed into the text. Sounds like a bad idea? Actually it works pretty nicely in many cases.

As an example, we can print the contents of a file and then check whether a certain word is contained in the text. To print a file, use cat. That stands for concatenate which means to add to the back of something, in this case concatenating the file content to the bottom of the terminal. cat file will print out the contents of file.

grep (meaning “global/regular expression/print”) will go through some text line by line and print out only the lines containing a pattern. If given the text

find me

leave me alone

please, find me, toogrep find will output

find me

please, find me, tooYou can plumb these two programs together. To take what cat outputs and input it into grep, use a pipe which is written as a vertical bar: cat file | grep find.

Variations: Not all consoles are created equal

There are a lot of different consoles out there. There’s bash, fish, zsh, cmd, PowerShell and more that I don’t even know of. And they all work slightly differently.

The biggest difference is between Unix shells (used in Linux and Mac OS) and Window’s variants. The programs and paths above are inspired by the bash, the Bourne Again Shell. On Windows, there is no cp program. But there are alternatives for copying files: in cmd it’s called copy, in PowerShell Copy-Item. Even paths are written differently. On Unix each folder ends with a forward slash, /path/to/a/file, while on Windows it’s a backward slash, \path\to\a\file.

But it’s not too bad. All consoles still provide you programs that you can call with options and flags.

Tricks: Complete historic kill

When you have to work with the terminal more often, you might benefit from some tricks that many consoles offer. Try them out to see whether they are supported in the terminal you use.

Most consoles will allow you to enter part of a file name and hit Tab which triggers them to fill out the rest of the file name for you. If there are multiple options that start with what you have typed so far, it won’t pick one at random. Hit Tab twice to show a list of available files. Continue to type out the file name you want until you can Tab it to completion. Completion usually also works for programs and arguments.

You can also quickly re-enter a command you have already executed, because most consoles keep a history. To go back in time, simply move up. You can also go down if you went past the command you wanted. If what you are looking for is a while back, you can, in some shells, press Ctrl+R and enter some part of the command. The history will be searched in reverse and the latest matching result will be shown. To select it, press Enter, to cancel Ctrl+C.

That last command, Ctrl+C, kills the program. For any program, if it won’t stop, you can go back to normal by sending that command. Note that the first time you send Ctrl+C, it will ask the program nicely to terminate. Most programs react immediately to this! If one misbehaves, sending Ctrl+C again will make the system stop the program, which can corrupt whatever the program was busy doing, though most of the time it is better to stop such a program anyway. Unfortunately, my muscle memory kills programs when I actually want to copy some text. Copying happens in some shells with Ctrl+Shift+C, pasting correspondingly with Ctrl+Shift+V.